A DIFFERENT SHADE OF BLUE:

HOW WOMEN CHANGED THE FACE OF POLICE WORK

“A Great Summer Read!” - Ms. Magazine

“A Different Shade of Blue: How Women Changed the Face of Police Work” tells the history of female cops in America through the candid voices of 50 women on the Seattle Police Department. As one of the first cities to hire policewomen in 1912, Seattle provides the perfect backdrop to tell an amazing story — women’s ongoing struggle nationwide to fit into the male-dominated police profession.

“A Different Shade of Blue” features three generations of women — black, white, Asian, Latina, gay, straight — speaking ‘on the record’ about their experiences on the streets and in the precincts. Hired between the 1940s and the 2000s, the women share stories of great heroism, from battling an armed assailant inside a patrol car to going undercover to catch an illegal abortionist in the days before Roe v. Wade. They also offer surprising views on affirmative action, and tell tales of discrimination and harassment that reveal how even today men continue to treat their female co-workers as second-class citizens. As the women recount their lives and experiences, they prove that female cops are a different shade of blue. And that difference has forever changed the face of police work.

In 2012 “A Different Shade of Blue” was translated and published in China.

A HISTORY OF FEMALE PIONEERS

Women have been struggling for equality in police work for over 100 years. The battle began at the start of the 20th century when suffrage advocates convinced city leaders to hire women because male officers were often unsympathetic to the plight of children and young women. The early female cops held the official title “policewoman,” and were often married or widowed socialites who saw police work as a way to help the less fortunate. Many were interesting characters like Fern “Stern” Wheeler who did astrological readings on the side, and Sylvia Hunsaker who helped keep a bankrupt city afloat during the Depression by cashing police paychecks with her own money.

Helen Karas (right) and Lillian Mitchell, the department's first African American policewoman, 1950s. Photo courtesy of Helen Karas and the Seattle Police Department.

For more than fifty years, policewomen nationwide remained segregated in ‘women's bureaus,’ received lower pay than male patrol officers, and needed college degrees to be hired while the men only needed high school diplomas. Unarmed and dressed in street clothes, these women frequently traveled the most dangerous neighborhoods pursuing runaways and aiding abused or neglected children.

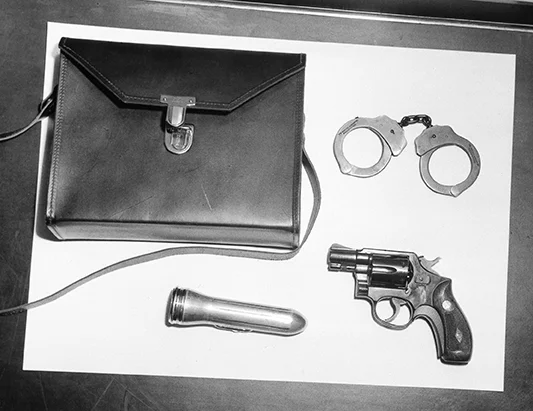

Specially designed handbag for the policewoman uniform, 1955. Photo courtesy of Helen Karas and the Seattle Police Department.

Change came slowly. In the mid-1950s, younger and more professional women arrived, among them tough-as-nails Helen Karas, urbane Karen Ejde, and future true crime writer Ann Rule, who served on the Seattle Police Department for 15 months before she was let go due to poor eyesight. This new generation dressed in professional-looking skirts and jackets, and carried guns in specially designed purses. Yet, policewomen were still treated like second-class officers and had virtually no opportunities for promotion.

“We really took on the burden of the welfare of all the children at risk in the city,” explains Asst. Chief Noreen Skagen, who hired on as a Seattle policewoman in 1959. “A lot of people accused us of doing social work, but we also made a lot of arrests. The mentality in those days could not even comprehend a woman in a police uniform in a marked patrol car responding to calls like male police officers. I had no problem with that because I was of that generation. I probably would have questioned the job if it had been in uniform patrol because to society at the time it was totally unthinkable.”

Police officer Toni Malliet in a publicity pose for the department, 1978. Photo courtesy of the Seattle Police Department.

Then, in the early 1960s, female officers in New York City sued for the right to take promotional exams alongside the men. When they won, policewomen across the nation were affected. By the end of the decade, segregation had ended and policewomen were assigned to units department-wide, and by the early 1970s they were finally allowed to compete head-to-head with men on tests for sergeant.

As the policewomen started moving up in the chain of command, one last bastion of male-ness remained — the world of beat patrol. When that barrier was finally broken in 1975, the first nine ‘female patrol officers’ made history by being hired and trained alongside the male officers. However, these women quickly learned that being trained to be equals was not the same as being treated as equals.

WHY ADAM WROTE THE BOOK

The idea for “A Different Shade of Blue” came to Adam during his time as a Seattle city prosecutor. One day in court, he struck up a conversation with a female police officer. She had been patrolling the streets of Seattle for almost 20 years, and she told him that when she began there were only a handful of women on the department. He asked her, “Did you face a lot of prejudice from the male officers?”

“Oh, yeah,” she replied. “The men were in three basic camps. Three-quarters of the guys were fine and gave us a chance. Then there were the old-timers who wouldn’t talk to you at all, and if they saw you in the hallway they made you walk around them. Then there was the third group who thought, ‘Hey, they’re here so we might as well date them!’”